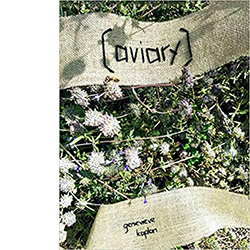

I originally started this point wanting to write out my thoughts on Genevieve Kaplan’s poem, “They trail there, they trail.” But it’s difficult to write about that poem alone without setting it in the context of the overall collection, [aviary]. The poem stands on its own, of course. How it singles out some specific yellow “thing” without actually telling the reader its source. “[I]t was the one yellow thing in the gray-green / world,” is one of the moments I especially admire. Like seeing a goldfinch out of the corner of your eye, so you’re not sure you saw a goldfinch, but it’s unmistakable you saw something yellow. Maybe the poem’s yellow is that peripheral sensation, how you “must have seen” something yellow, and, suddenly, your margin of sight is your focus. Maybe it’s about seeing some unmistakable yellow flower (with “narrow curling tendrils,” to pull from how poem describes the flower), and its yellowing intensity is so loud it takes over your vision. And, for the sake of this single poem, I end it wondering if I need to understand the kind of yellow it is? Are there ways to describe a specific yellow that reaches past just calling it “yellow”? And what about the simple fact that that yellow contrasts to all the gray-green of these woods? And how the sensation of yellow feels like entirety, but it’s not the entirety of the scene.

Questions like these, in particular the ambiguity surrounding what should be something specific (like the yellow “thing”), is part of Kaplan’s operating mechanism in (aviary). To refer without specifically referring to, say, birds. “They trail there, they trail” might identify “the one hummingbird shooting past,” but, generally, the book leaves out kinds of birds in favor of what it means there are birds around us. That people have ready access to birds. Their habits and behaviors. Their actions. And, it seems to me, Kaplan would encourage people to watch how birds watch nature. Like rather than poems that delight in the particularity of a certain bird, reveling in the bird’s specific features, or its presence, or its stature, Kaplan places the poem amidst the birds, and how the world around them forms. And, remarkably, how language might express this.

the boundless animals over

(from “They trail there, they trail”)

short twigs, picking up the short twigs and carrying them along

in their short arms, short beaks. who drift in patterns, in waves

of sound, and echoes and cannons of them, the sirens

that (in effect) have been surrounded by (the dull roar of yellow) the only lacy

thing, the only fine thing, the only petaled thing the gray

path slowly curving to the right, to the left, curving away, the only

only soft thing

And how Kaplan can develop this perspective on birds over the course of the book is one of the larger pleasures of reading through (aviary). There is an undeniable intention to teach the reader what bird-perspective might be. Or I think of it as a bird-perspective, because I’m not entirely sure what to call my reading. Like what is the book’s destination? Kaplan’s language is doing something; it’s easing me into something. A way of seeing? A way to be aware while in nature? I might argue, this is what language might look like if it were voiced by a bird’s perspective. Whatever the something Kaplan is doing with the language in her book, its indecipherable origin is kind of like the “it” in Ashbery’s poems. Whose antecedent or referent you feel like you should know (and in a generous reading you’re pretty sure you do know, or maybe you just “know”). Whatever the state of knowing Ashbery puts you in, you learn to accept the “it” as something interesting enough to write a poem about. And in Kaplan’s situation, what I might call the “it” of the book has definitely localized to a kind of animal, and that informs the lens I apply to her language. At the very least, the book is concerned with birds. Consider the title of the book. Consider the many references to birds and nature. Consider what I would argue is a sequential shift in voice from human-ish observer to bird-ish observer—a shift establishing an overall arc for the book.

With the book’s first poem, “The birds had taken over,” the poet is simply observing the birds that appear in her yard. It’s a straightforward scene from her dining room window.

and that was enough pleasant talk

(from “The birds had taken over”)

a chirp, there

a peck and a scattering of seed

and they get smarter by the hour, defined

by the sun and the shadow

The poet reports on the birds’ actions. Their chirping. Their haphazard feeding. There isn’t the doubling back, like how “thing” keeps reappearing in the second half of the above quote from “They trail there, they trail.” The book’s first poem doesn’t have the chaotic details from nature. It feels focused, or framed. The poet finishing her breakfast, or whatever the occasion for this “pleasant talk,” and now the birds take center stage to that domestic scene.

It reminds me of Jennifer Chang’s poem, “The Innocent” (found in Best American Poetry 2022). For Chang, the elaboration of a family is more explicit. They observe a pair of robins who have set up a nest inside a neighbor’s honeysuckle. And, as a pandemic poem, the poet’s family has nothing to do but watch the eggs’ hatching. It’s a recursive image serving both for occasion (watching how deadly the cycle of nature can be, and all from our window!). It also serves as an analogy to the lockdown. What hope or continuance felt like while we were all trapped inside. And what both Chang and Kaplan touch on is the state of mind while watching birds. It’s a certain kind of temporality. Realizing the bird might be in your domestiic space, but it’s not a domesticated animal. And both poets stylize the language in these poems so the birds are included in a scene that feels familiar. And for Chang’s poem, the unfamiliar is something to resist, like the less familiar part of nature where a robin gets killed by their pet cat, but she’s going to keep that fact outside the familiar arrangements. Consider how Chang minimizes this event, and how that minimization fits into her reflection back on that time of the pandemic.

It was easy

(from “The Innocent”)

to mistake the bared skeletal pinions

as lawn clippings, old leaves. That circle

in the grass, a massacre of feathers. That

terrible cat. It was easy to lose my mind.

One neighbor said, let’s not tell the children,

why know the world as always fated

toward remnant.

Maybe I shouldn’t say Chang is minimizing here. But it feels like that to me. How quickly she moves past each of the details. “That circle / in the grass, a massacre of feathers. That / terrible cat.” There’s an unmistakable violence to be inferred from these descriptions, but the poet isn’t dwelling on it. She’s more moving past it quickly. Kaplan’s quote uses a somewhat similar strategy, quickly moving through impressions, “there / a peck and a scattering of seed / and they get smarter by the hour.” I’m interested in how both Chang and Kaplan can be so brief with their impressions, and yet the language still involves me in that moment. And I’m not entirely clear how it does that. Is it the domestic scenes I’m all too familiar with? How I’m reminded of the breakfast table I sit at every morning, looking out at my backyard? Do I linger because I feel like I know these moments? Or is there something in the style?

However it is, it’s significant to me, because I want to argue Kaplan’s [aviary] pushes the style in each of her poems from thick to much thicker as she moves to what I’m calling a bird-perspective. And that thickness is part of how she sees birds seeing the world. It’s a mimetic take elaborated on through a slowly shifting style that changes from one section of the book to the next. So that eventually the poems account not only for how the birds see, but where they would see. The poems move from the poet’s backyard to a more pastoral setting, where “pastoral” is not equivalent to nature, more that space between nature and the domestic. It evokes the natural world but in a contained, bordering on curated, fashion.

When I was in grad school, I argued with a professor about whether pastoral poems could occur in a city. I was using a lot of nature in my poems, and thinking particularly of the logic implicit to the natural image. For instance, in a life that feels chaotic, the cycle of seasons can feel stabilizing in their regular occurence. If there was a tradition of nature poems, I wanted to participate in that tradition. Or I wanted to think more carefully about how the details of the nature poem might be thought through further. It seems, however, that nature is not really essential to the pastoral poem. Meaning, the natural setting shouldn’t dictate the single lens for reading the pastoral poem. I understand the pastoral is also a social situation, so the reader recognizes “the people in this poem are going to act like we were all with each other in nature,” a kind of togetherness. Especially when people are together under ideal conditions. Perfect weather. A softened setting. And so maybe the pastoral is just about a group of people gathering, like when people isolated together during the pandemic. And you were just so grateful you could sit in the backyard with other while listening to birds.

And what I see in Kaplan is that “together” here doesn’t really feel like people being together, and definitely not a shepherd boy and his shepherd friends sitting around listening to the main guy tell stories. Instead, it’s the poet and her companions, who are all birds. And the poet’s special gift is to put language to how she sees birds observing and existing in the world. Like she was pulled into the bird world first by simply observing their movements while she ate breakfast, and then as her watching was more sustained, her perspective broadened, so she was looking at the birds as behaviors or life habits or the continuous series of choices a bird makes in its life. Which compelled the poet to follow the birds. Until the pastoral space she shared with them moved from her backyard to a city park to one of those patches of woods that border a city park. Something forest-ish, but not entirely forest. A place where the poet could be taught by the birds how to look, what to attend to, what an animal needs, how an animal survives or feels entertained. Or what is it animals do? And I like this as the question Kaplan’s book leads to. Because animals do so many things. And her poems, especially where I see them reconstruing what an observation is, makes what animals do feel like a sustained activity that is so different from the human explanations I project upon them.